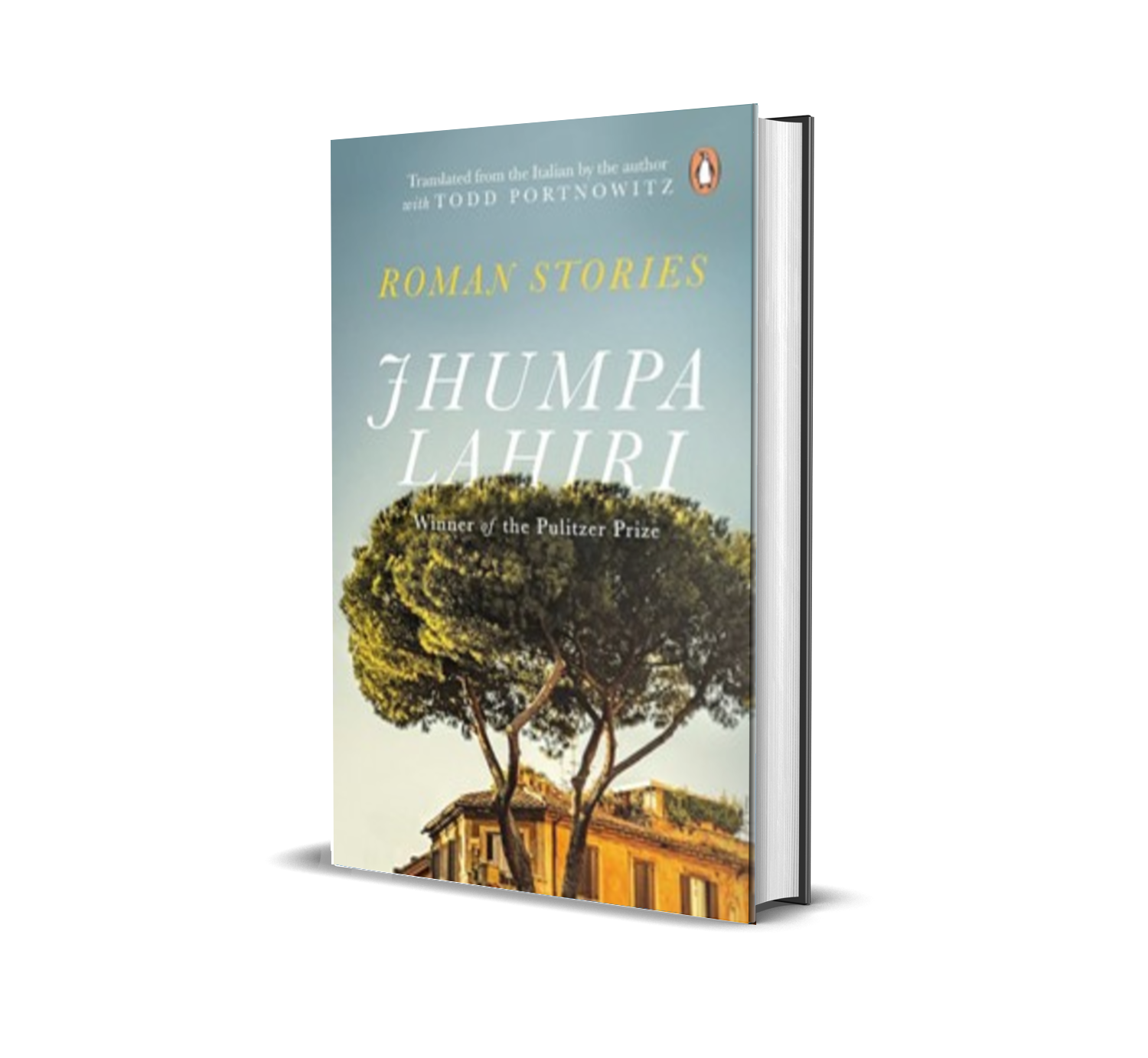

In her latest collection of short stories, "Roman Stories," Jhumpa Lahiri takes readers on a journey through a Rome distinct from the one immortalized in Fellini's films and the image of patrician women in black dresses. Lahiri's Rome is a city of new beginnings, where immigrants arrive on boats, grieving parents confront the loss of their 12-year-old son, and widows experience solitary living for the first time.

Since her move to Rome in 2012, Lahiri has boldly undertaken one of the most daring literary experiments of our time by writing exclusively in Italian. Within this collection of 13 stories, Lahiri has personally translated all but three critical ones, which were translated by Todd Portnowitz.

The theme of feeling like an outsider, a recurring thread in Lahiri's work, remains a prominent feature of this book. The stories are set on the outskirts of the city, with women returning to Rome to relive old memories, and men congregating at outdoor trattoria tables. "Roman Stories" conveys an essence that casts a shadow over both the ground and the uncharted sky.

The immigrant experience is central to the first section of the book, focusing on those who come to Rome seeking a better life. These newcomers are often referred to politely as "la moretta" or heckled as "ragazza" on the streets. They arrive in long cotton dresses and veils, reminiscing about their homelands with palm trees, crows, and dusty roads. In one of the most poignant stories, "Well-Lit House," a young father of five reflects on his journey to Rome after the war claimed his grandparents' lives. He recalls the white butterflies dancing above the sea, seemingly leading the way. However, upon arriving in Rome, the only creatures to greet them are cicadas, which startle his wife.

Reading Lahiri's work amid news about millions of displaced Palestinians resonates deeply, underscoring the theme of "othering" and the impact of minor humiliations on large-scale conflicts. Notably, the book does not overtly specify the nationality or ethnicity of its characters, emphasizing instead the emotions the city evokes.

The stories explore various aspects of life in Rome, from foreign correspondents and diplomats to mothers of international schoolchildren, offering glimpses into the city's diverse social circles. Lahiri's narrative perspective shifts from young girls to middle-aged men fantasizing about affairs, to third-person observers, resulting in some uneven storytelling moments.

Remarkably, the book balances architectural descriptions with the city's rich traditions, routines, and culinary delights. Readers will find themselves immersed in the romantic piazzas, bridges, derelict archways, and local culinary delights.

While some of the stories may feel long-winded, the final section of the book provides a punch of emotional depth reminiscent of Lahiri's Pulitzer-winning debut work, "Interpreter of Maladies." The last story, "Dante Alighieri," reflects on the passage of time and the graceful acceptance of fate, echoing the Latin phrase "Incipit Vita Nova" (And so begins a new life). It's a profound reflection on a city proud of its aging churches and seasoned faces, reaffirming Jhumpa Lahiri's unique storytelling prowess.